Caring Too Much: Identifying Signs of Distress in your Patients’ Caregiving Team

by Wendy Benson

When working with patients and their families, I’ve learned over the years that many family members don’t see themselves as caregivers. We all give care at some point, that’s understood. But there’s certainly a difference between what we identify as a care team, and who patients see as part of their care team.

It’s an interesting exercise – consider asking your patients who they consider as part of their care team – do they reference those on their medical team? Their loved ones? Or both?

Regardless of whether or not family members identify as caregivers, giving care can be stressful and overwhelming for those not in the healthcare profession. Quite honestly, it can be equally as stressful even if you are in healthcare!

Caring for loved ones brings a different level of abilities: increased responsibility, accountability, reliability, even feasibility. More often than not, while you are caring for your patients, their caregivers are navigating unfamiliar territory with considerably little experience. Because our patients’ loved ones keep them safe, out of the hospital, and act as an extension of your own team in many ways, it is important to recognize signs of distress, and ways to help.

While you’re caring for your patients, who’s caring for their family?

It may be difficult to recognize when your patients’ caregivers are overwhelmed, especially if you’re only seeing your patients at office visits.

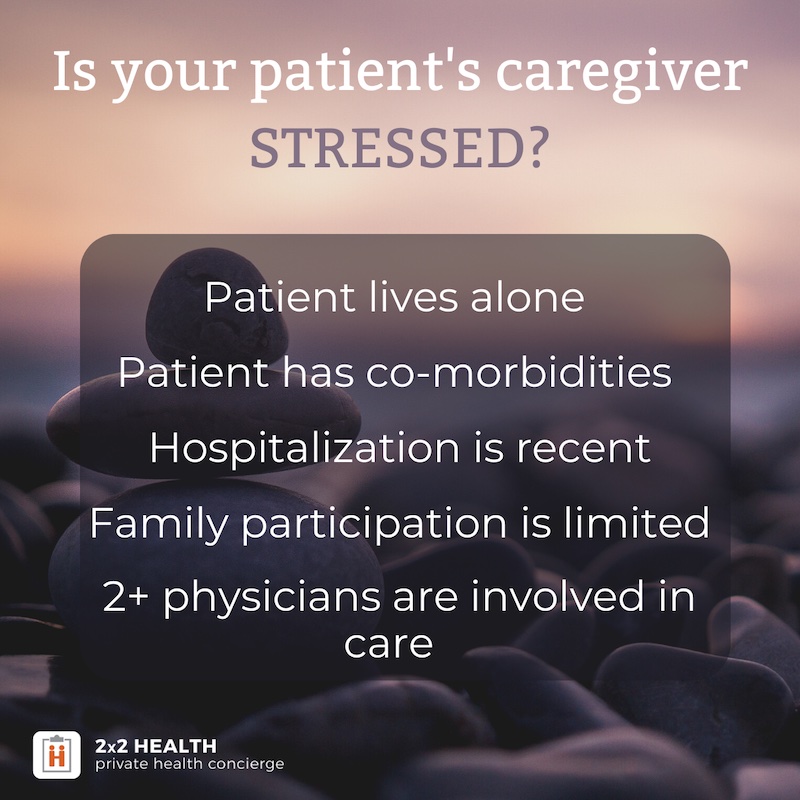

If your patients and their caregivers are managing two or more of the following, they may need help:

- If they’re caring for someone who lives alone or wants more independence

- If they’re caring for someone who has been to the ED twice in 6 months

- If the patient has several different specialties as part of their care team (co-morbidities)

- Managing multiple medications and susceptibility

- Two or more physicians involved in their care

- 60+ years of age

- Hospitalization within the last year

- Recent changes in medical condition

- Limited proximity or participation of family

If you sense fear, concern or anxiety from your patient’s caregiver, the family may not know where to turn or they don’t have the right support. Perhaps they aren’t familiar enough with other resources and services that may be able to help them.

Of course, it’s often much easier to talk about a patient’s health than it is to discuss the caregiver’s health. Initiate the conversation by acknowledging and validating their experiences, and offer insights based on your own experiences: “It would not be unusual for someone in your situation to feel overwhelmed – and when I’ve had patients’ family members overwhelmed in the past, this is what they’ve found helpful…”

Caregivers may find some relief from their everyday stress through the following:

- Talk to someone else every day. Maybe it’s a text, maybe it’s an email. Even if someone’s not a talker, it’s important for them to stay connected to others that are important to them.

- Let go of guilt. Don’t harbor those things – “it’s hard to feel guilty when you’re feeling gratitude’ (focus less on the guilt, more on the gratitude); if you are struggling, talk to a professional. It’s underutilized.

- Exercise. This doesn’t have to be a full-blown workout. Take the dog for a walk, get some fresh air.

- Consider reducing caffeine. Doesn’t mean give up coffee altogether, but maybe forego that fourth cup of coffee because the anxiety level is high enough already.

- Ask for – and accept – help. But it’s got to be the right kind of help. What kind of help is appreciated and valued? And be specific with the right kind of help.

A really good caregiver can often keep patients safe, healthy and out of the hospital. A great caregiver is one that prioritizes taking care of themselves and others equally, and must be considered an extension of the care team for your patients. It’s much easier to keep patients safe and healthy when those giving them care are safe and healthy as well.